Connor is a food crafter just getting back into the business after his mother’s death. To cope with his grief, Connor spends day after day recreating her potstickers, but they are never quite what he remembers. To move on with his life, he will have to confront his past.

This is how Connor renders a pot sticker in paper: He crinkles and crumples a circle of white construction paper until it is soft and pliable. The circle is large enough that a tangled ball of shredded paper fits inside with enough room for a generous lip. And it needs to be generous because, unlike dough, paper doesn’t stretch. The ball doesn’t have the heft of a mix of jiucai and ground pork, but it will still push out against the paper once it is folded. He rings the paper with glue, not water as he would have with a circle of hot-water dough. Carefully, he folds the paper over and presses down on the edges to form a lip around the semicircle. Glue seeps out, which he dabs away with a small towel. This obviously never happens with water on hot-water dough. Fold by fold, he crimps the lip so that the semicircle is now a plump crescent. With hot-water dough, folds would just stick together, but this is paper. The folds accordion, and he dabs each with a droplet of glue then presses them all flat. The work is meticulous. When he’s done, the body isn’t the right sort of plump and it doesn’t dimple in the right way. The technique, though, is sound. It takes minutes to make each pot sticker. He makes three.

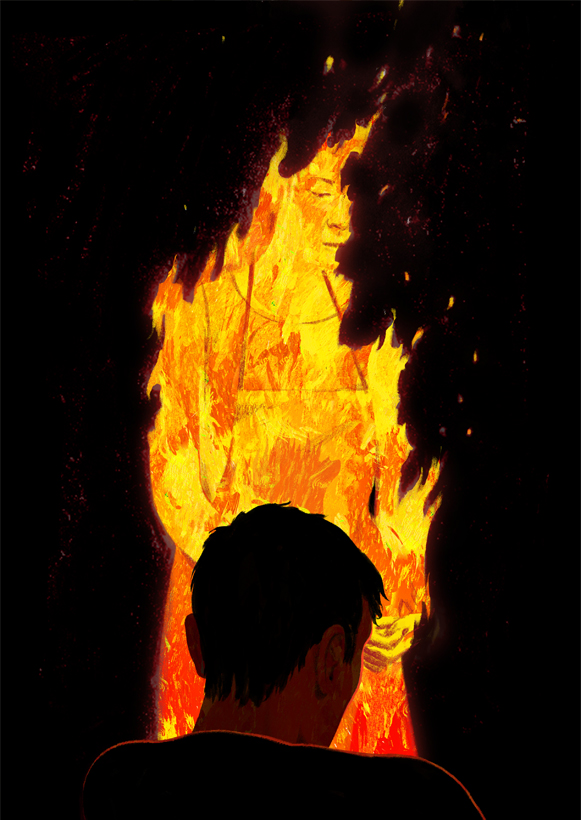

This is what Connor does with three pot stickers made of paper: He stuffs them into a cracked mug. The match hisses when he strikes it against the matchbook cover. It bursts into flame and, when it touches the pot stickers, the flames spread. Golden tendrils reach up, covered by wisps of smoke. The pot stickers blacken and shrivel into the mug. Unlike the first seven times Connor has done this, he’s remembered to open a window and take the battery out of the smoke detector. A piercing beep does not slice his ears. The faint haze in the kitchen clears.

It’s not that Connor believes his mom will actually get the dumplings or even that his mom is out there somewhere waiting for burnt offerings. The economy of the afterlife if it existed would have to be pretty screwed up, with people burning paper representations of money and planes and cell phones. Still, he wants to show her he’s learned how to shape a dumpling, even if he still hasn’t figured out the exact filling his mom made.

Buy the Book

Beyond the El

The band singer’s voice is this slinky, sinuous thing, a voluptuous baritone that nestles around every word he sings. It’s almost enough to distract Connor from the singer’s broad shoulders and the graceful taper to his waist. Those could just be gifts from the singer’s elegantly tailored suit, but Connor has also seen him with the jacket off, bowtie unraveled, collar unbuttoned, and sleeves rolled up. If anything, the suit hides the singer so Connor can pay attention to the song. Connor knows the handsome band singer’s name, Nick, but he’s better off thinking of him as the handsome band singer.

To the customers in the restaurant, the handsome man crooning jazz standards and the piano and bass backing him are just set dressing. Nick could be declaiming Wagner or heavy metal and only one who’d notice would be Connor. Everything on the singer’s tiny stage is just a backdrop to the real show, the food.

Meals are prepared at the table. Diners in exquisitely tailored dinner jackets and impeccably fitted gowns sit at small round tables. Servers dressed in crisp white shirts and pleated black trousers fulfill their every whim. At one table, a diner’s steak, already patted dry, its flavors already adjusted, sits uncooked on a plate. White streaks of fat alternate with dark red streaks of muscle. The server passes her hand slowly over the steak. It transforms from raw to medium-rare. Clear juice seeps out and is reabsorbed at the server’s command. Another slow wave of her hand and the steak is seared on both sides. At other tables, teams of servers work together to transform and plate ingredients in a strict timeline lest a foam collapse or an ice melt before it can be savored.

Connor is back of house, prepping. Servers sweep in and out. They place orders and carry away plates loaded with the prepped materials they will transform before their diners’ eyes. The band singer’s song is a sinuous thread weaving through the thud of knives, the whir of motors, and the staccato bursts of servers’ calls and preppers’ responses.

A pile of carrots sits at his prep station. It doesn’t even take a glance for him to know how each carrot will taste. One by one, he takes each carrot and adjusts it to its bliss point, that place where it is the most like itself. He crisps its texture, adjusts its color, and intensifies its flavor. Some days, rather than hitting the bliss point, his job is to layer in the bite of pepper or the decadent unctuousness of foie gras. Today, though, all he has to do is make them all the perfect carrots everyone desires but no one can grow. That’s not anywhere near the limit of his abilities. If you leave the trade and then return, though, you start back at the bottom. Leaving to take care of your catatonic mother may be laudable, but also irrelevant. So, instead of working out on the floor, what he does for now is rewind time. Stopping time is impossible. All things fall away from their bliss points as they inevitably decay and rot.

The maître d’ strolls up to him as he is chopping, replenishing the mise en place, making it fresher than fresh. She’s never back here. Connor can feel her gaze bear down on him, but she waits until his knife no longer blurs before she says anything.

“You’ve been requested, Connor. Get into your service uniform.”

“Can they do that?” Connor turns to catch the sous chef’s gaze. She nods back at him. “And with no notice?”

“Well, you’re overqualified for back of house. And if they pay enough . . .” The maître d’s wry smile tells him all he needs to know. “You understand tonight’s menu.”

It’s not a question, but Connor still rolls his eyes. He has been preparing this menu literally all night. Besides, with a couple exceptions, this restaurant isn’t that ambitious. And no one orders the ambitious items.

“Good.” She pats Connor on the back. “Go get changed.”

The customer sits at the most sought-after table in the restaurant. It’s in a private but spotlighted corner. Noise-canceling hardware embedded in the walls puts the customer in her own private world. Whoever serves her, though, is performing for the entire room. Servers draw straws to avoid this table. Sitting at this table with no advance notice must have cost quite a bit to soothe the ego of whoever originally reserved it.

Connor is now dressed in his crisp black-and-whites. As he crosses toward his customer, the band singer starts into Bernstein’s setting of the Ferlinghetti poem, “The Pennycandystore Beyond the El.” A jazzy piece of atonality, this is less crooning for atmosphere than the band singer flashing his expensive conservatory training. The band singer’s eyes sparkle as his gaze meets Connor’s. A smile spreads across the band singer’s face. Connor can’t help but think the band singer is singing just for him. It’s a fantasy he knows he should bury, but he can’t.

The fantasy shatters when he sees who has requested him. His sister sits at the table alone, her back to the corner, browsing the menu.

Somewhere, right now, a garage door is rattling open and a young boy perks up because it means his big sister has to stop beating him. Their parents cook—not craft—the sweet and fried stuff Americans expect when they think “Chinese food.” Americans expect “Chinese food” cooked by the Chinese to be cheap, so his parents run the restaurant without employees to help them and they work twelve-hour days. Their children go off to school before they wake and are ready for sleep by the time they come home. Sometimes, they are too late and the young boy has already fallen asleep. There are many weeks where the boy sees his parents only on the weekends. His parents have no choice but to leave it to his sister to raise him by herself. This is a lot to lay on a thirteen-year-old girl. None of her friends have to raise their kid brothers. If she thinks having her kid brother dumped on her full-time is unfair—even if it does not justify beating him—she has a point. The rattling garage door means their parents are practically home. His sister never hits him when their parents are at home.

When Connor was that boy, perking up just made his sister angrier maybe because it meant he’d get away it. He still has no idea what “it” was. Changing the channel on the TV, not changing the channel on the TV, pouring a glass of soda for himself but not also for her, pouring a glass of soda for himself and also for her: all got him beaten. Telling their parents what she was doing really got him beaten. She never left any bruises, though, and their parents never believed their angel could ever lay a hand on him. Then again, that was also what they needed to believe.

Connor’s gut roils as he approaches the table. His sister has pulled any number of stunts on him, and this could be yet another one. He has always gotten the impression that her stunts fill some need in her that he can’t understand. Her best—or worst—stunt to date was to fire Mom’s part-time healthcare assistant once Connor had agreed to move back and take care of Mom part-time. It would have looked bad to the relatives back in Taiwan, his sister insisted, for someone outside of the family to take care of Mom. He couldn’t afford to hire an assistant by himself and his father—Connor knows people his age with grandparents who are older than his father—could barely take care of himself. So, Connor ended up taking care of Mom full-time instead. He’d be lying if he said he wasn’t relieved when she finally did die, even if being relieved makes him a monster.

The urn with Mom’s ashes has been sitting on the mantel of his sister’s fireplace for months now. That it’s taken his sister this long to show up is downright sporting. She might really just be here for dinner. That flicker of hope is completely unwarranted, but he can’t help himself.

“Prue.” Connor stands in front the table. For her, he’s careful to iron all inflection out of his voice.

“I need you to renounce your citizenship.” She says this as casually as someone who liked him might say hello.

And hope dies again. Connor, though, does not miss a beat. He is a food-crafting machine.

The request for her order falls smoothly from his mouth. She orders the most outrageous thing on the menu, the scale-accurate model of the Chrysler Building. It’s only there to make everything else look reasonable and affordable. He is aghast, but he merely nods and smiles. His heels click, his body pivots, and he’s gone to the kitchen to gather the ingredients before he realizes he’s even moved.

The raw materials that will become the Chrysler Building fill both tiers of his cart. Inertia gives it a mind of its own as he steers it around the tables in the dining room. The maître d’ stops him.

“Sure you want to do this by yourself? I hear the staff here is top notch.” The maître d’s gaze flicks over to the handsome band singer. “Besides, you already have his attention. Showboating isn’t going to make him notice you more.”

The Chrysler Building normally takes five servers and three table bussers to pull off. Conner isn’t building it by himself to prove anything to the handsome band singer, not that he’s against showing off to him. In the moment of reflection before he responds, he realizes he’s not even doing this to prove anything to himself. If the customer were anyone but his sister, he might have put a crew together and put up with their help.

“No, I can do it.” He wants to push on, but the maître d’ reaches for his arm.

“Obviously, but that’s not the question.” Her smile is warm and still something Connor’s not used to. “Do you want to do this by yourself? There’s a crew of trustworthy servers and table bussers who’ll help you in any way you ask.”

“I don’t think that’s the question, either.” Connor pushes on and, this time, the maître d’ lets go.

Prue smirks when she sees the cart. Something tightens inside Connor, but he forces her expression to pass right through him.

The Chrysler Building is a deconstructed paella composed of discrete floors that become ever lighter and more delicate as they approach the building’s crystalline spire. Garlic and saffron perfume the air as he prepares all the layers from the grouper at the bottom to the clear tomato distillate at the top at once. Various proteins transform from raw to poached as a deft gesture of his hand lifts them off their plates. At a glance, a pot of water begins to simmer and the water is infused with flavors from fish bones and shrimp shells. Within minutes, the water is transformed into savory stock. Grains of rice swirl about an invisible center. They swell and congeal as they absorb the stock that he makes rain down on them. Meanwhile, with another deft gesture, tomatoes dissolve then evaporate. Their clear condensate drips into a gelatin that Connor has crafted in the meantime.

Sweat trickles in tiny beads down Connor’s face and back. The building’s foundation, impeccably poached grouper glued into a slab, quivers on a gold-edged plate. As he lowers the next layer, Prue slides documents onto the table.

“Durable power of attorney.” Prue offers Connor a pen. “Sign it.”

For a moment, Connor’s torso stiffens, his back ramrod straight. His rib cage shrinks but doesn’t expand again. Whatever’s inside twists. Asking him to renounce his citizenship was just a bit of anchoring, then. It’s the same trick the restaurant pulls when they put the Chrysler Building on the menu. Prue might want Connor to renounce his citizenship, but signing a durable power of attorney sounds so much more reasonable in comparison. Not that letting Prue act on his behalf in legal matters is a good idea. She still hasn’t told him what this is about. Then again, he also hasn’t asked.

He just keeps on multitasking. Everything has to happen at just the right moment or else some emulsion will fail to set properly or some foam will collapse. This is why it takes a team to build the Chrysler Building, or would if he weren’t so intent on proving himself to the uncaring audience. Prue sets her pen on the document. As he continues to craft, she just sits there, her arms folded across her chest, waiting.

He falls behind, of course. Not even when he was at his best could he maintain a stock at its bliss point, stabilize a foam, and place a slab of emulsion on an increasingly precarious stack of them at the same time. The foams are stiffer than they ought to be. The transparent flakes of flavored rice emulsion are rough and coarse rather than straight-edged and delicate. He sets them in rows to create the spire with as much precision as he has time for. The rows, one overlapped on top of another, are almost the narrowing concentric arcs they should be. The triangular flakes don’t always point at the tangent of the curve like they should. The effect is not that Art Deco sense of utter craftsmanship. When one is just trying to prevent the building from sagging or, worse, toppling over, one makes trade-offs.

The spire floats just above the top layer of gel. With deft hand gestures, he guides it onto the clear tomato-saffron distillate. As he does, Prue grasps at the durable power of attorney. The papers skid across the table before she catches them. The Chrysler Building wobbles.

“Look, this is just so I can tell the probate court that you want your third of the estate to go to Dad. I know you don’t want it to go to me.” She rolls her eyes. “If you don’t trust me, get a lawyer to draft something that says the same thing.”

It takes effort to steady his breath. He is a rubber band being wound tighter and tighter. Prue hasn’t so much as messaged him since the funeral, much less mentioned Mom or probate. Connor saw Mom’s will once, but it must have been lost if probate matters. If they had the will, they’d just execute it. Also, some of Mom’s “estate”—their parents aren’t not exactly rich—must be in Taiwan. Grudgingly, Connor has to admit that having a Taiwanese citizen—to the extent that that’s even a thing—take care of Taiwan probate might be easier. That doesn’t mean having Connor renounce his US citizenship and repatriate to Taiwan makes any sense. Giving his own share to Dad does, though. If anyone had bothered to ask Connor what he wanted, that’s what he would have told them. As best as he can remember, it’s also what Mom wanted in her will.

Connor sets the spire in place. The building hardly sags at all.

“Sure.” His voice is as smooth and level as any layer of emulsion in the building he’s just constructed. “I’ll mail it to you.”

“Excellent. Let’s settle up.” She pushes back in her chair. “Check, please.”

The rubber band snaps in two. It whirs as it unwinds. Its ragged ends flail where no one can see them. They slice the air, whistling with each strike. Their energy is spent in an instant and they lie limp in an unruly tangle.

“Very good.” He nods, all inflection ironed out of his voice.

With a click of his heels, he pivots to retrieve her check. His sister does not leave a tip.

Connor sits slumped on a bench in the restaurant’s locker room. He’s half-dressed. His pants are unbelted and unzipped. His shirt hangs unbuttoned off his torso. Elbows braced against his knees prop up his body as he stares at nothing. Any number of servers and table bussers have asked him whether he’s okay as they changed out of their uniforms and back into street clothes. Connor merely croaks that he’s fine, his gaze still aimed at some point beyond the row of lockers he faces. They all look at him, their eyebrows rise, and they sigh before carrying on with their own lives.

He’s still sitting there like that when the handsome band singer shows up. Nick is half out of his shirt when he notices Connor. The shirt hangs off his body by one sleeve.

“Don’t tell me you’re fine, Connor.” Nick crouches in front of him.

“Oh. Hi, Nick.” Connor looks up for a moment, then breaks eye contact. “Congratulations. Now that you’ve passed the audition, are you leaving us?”

“Oh, that. It’s just the district audition. I still have the regional and, if I’m lucky, the national after that.” Nick shrugs. “I’m sorry some customer didn’t even touch your work.”

“Not some customer. My sister.” Connor is too tired to resist any longer, so he lets the handsome band singer fill his gaze.

For all the width across his thick back and the way his chest and arms pop, Nick isn’t built like some statue of Hercules. He’s soft enough to read as human rather than demigod. His mouth opens and closes a few times before he finally speaks again.

“So, that’s your sister.” His gaze narrows, his lips purse, and distaste spreads across his face. “Am I supposed to slap you now?”

“What?”

“You told me once that if you ever let your sister railroad you into anything again, I should slap you.”

“Oh, right.” He actually had said that. They chat in the locker room surprisingly often. “No, I really do want my share of my mom’s assets to go to my dad. It’s what she would have wanted. I just need to get a document from a lawyer to that effect that will hold up in court.”

Connor rolls his eyes at Nick’s skeptical gaze. The handsome band singer has heard too many stories about Prue. Granted, Connor was the one who told him all of them.

“Can you afford the consulting fee?” Nick stands and finally pulls off his shirt. “I can spot you the money. Pay it back when you can.”

“No. I got it.” Connor yawns. “They’re letting me pull extra shifts here.”

Nick’s gaze does not get any less skeptical. He goes back to his locker and pulls on a T-shirt. It manages to be both baggy and revealing on his body. Only now does it occur to Connor that he should change out of his uniform, too.

“Want a ride home?” Nick pulls on a pair of jeans. “You look like you’re going to fall asleep on the bus again.”

Back in civilian clothes, Connor shuts his locker. Now that Nick is fully dressed, looking at him doesn’t feel nearly as illicit. Nick, for his part, has chatted with Connor in every possible state of undress including naked. Illicit may not be how looking at Nick is supposed to feel.

“No, I’ll be fine.”

It’s cold out, and that’ll keep Connor alert enough to get on the bus. Sometimes, he gets lucky and he wakes up in time for his stop. Other times, well, he’s never not made it home.

Nick frowns again. He pulls on a thick coat. It ought to obscure the taper from his shoulders to his waist. It doesn’t.

“Look, if you ever want a ride—”

“I’ll ask.” And, after an awkward pause, he adds, “Thanks.”

“Well, safe travels, Connor.”

Nick slams his locker shut and leaves. His walk is jaunty, stepping in time to a sea shanty only he can hear. Connor collapses back onto the bench, but then forces himself back up and puts on his coat. It’s freezing out, and the bus waits for no man.

The lawyer that the Taipei Economic and Cultural Office recommended to Connor is three bus transfers away. It takes Connor several hours to get to her office. He shivers off the snow then hands the receptionist a check. The consulting fee has to be paid in advance.

The lawyer’s office is cozy and warm. A large desk sits between them. The lawyer is way more ambitious than he is. She leans forward, asking him to come back with documentation about his family and Mom’s assets. When it becomes clear that he can’t afford any more than this visit, she scribbles out something that her office will make presentable for him to give to his sister. Her reluctant expression and audible sigh screams “against my better judgement.” Maybe it’s just pity, but he’s not proud.

Shifts at the restaurant come and go. If Connor wants to chop vegetables and adjust the texture and flavor of meat for hours at a stretch, his fellow servers are happy to give up those shifts. There are a couple rough weeks where Nick is gone, preparing for and, ultimately, winning his regional auditions. More than once, Connor’s not sure how he’s gotten home.

The time Connor doesn’t spend at the restaurant, he spends in his own kitchen, a thin strip of linoleum flooring at one edge of his tiny apartment. Mom’s pot stickers won’t recreate themselves. The extra shifts at work now pay for flour, pork, vegetables, and spices. He figured out the hot-water dough a while ago. As winter thaws into spring, he is still puzzling out the filling.

The dough rests in a bowl covered by a damp cloth. In another bowl, he mixes pork, scallions, ginger, soy sauce, and sesame oil by hand. A savory, salty meatiness with a slight jab of heat fills his mouth as the mixture squishes between his fingers. He frowns. The flavor is still not what he remembers. He tamps down the fire from the scallions as he works the ingredients together. In retrospect, he should have stuck with jiucai.

He rolls out the dough into a long snake. One by one, he rounds the small clumps he breaks off between his palms. Forming the tiny balls of dough used to be his job when he was too young to pay attention to how his mom made the filling. Just like he’s doing now, his mom would roll out each ball into a circle, put in a dollop of filling, then crimp the circle into a dumpling. When he’s done, several dozen of them form a neat grid on the floured table.

He crafts rather than steams then fries the dumplings. No one wanted Connor to spend the years training to be a food crafter. Well, except for Connor, but no one cared what he thought. Since he is a food crafter, though, there’s no point to not taking advantage of that. Whatever made Mom’s pot stickers Mom’s has nothing to do with a bamboo steamer or frying pan.

The dumplings bobble into the air. They plump with steam and are seared so that they all have crunchy, slightly oily, and savory crusts. Unlike anyone using a steamer and a frying pan, he can hit the bliss point exactly every time.

He slides a plate beneath them, then lets them fall. Juices dribble down his chin when he tries one. It’s fine, perfectly cooked even, but it’s no more than that. It doesn’t taste like Mom’s. They never do. He can diddle with the flavors. Hell, if he put his mind to it, he could make the dumplings taste like a crisp, tart apple tinged with cinnamon and cardamom. What he can’t do, at least not yet, is make them taste like the ones he remembers, the ones his mom made when he was fourteen when she wouldn’t show him what to do no matter how much he begged.

He pulls a journal out a drawer. The cover is tattered, and variegated pages paint swirls along the edges formed when the pages stack as the journal is shut. A bookmark sticks out the top. Each page has the flavor of a batch of dumplings he has made. This way, he never tries the same dumplings twice. He opens it by the bookmark to a blank white page. He scrawls today’s date on it, then infuses it with the flavor of this batch. Streaks of green flow down the yellowing page.

The journal goes back into the drawer. The dumplings go into a resealable plastic container. They’ve become surprisingly popular at the restaurant’s staff meals. Connor, however, can’t make himself eat them.

The maître d’ hands Connor a notebook that has “Mom’s recipes” written in his sister’s precise handwriting on the cover. Connor’s hands shake so much, the notebook vibrates. His heart pounds. The notebook is probably not what it looks like but, as always, he can’t help hoping. He pushes past her and several startled servers, and nearly crashes into a table busser as he sprints out of the dining room.

Customers in their elegant dinner jackets and evening dresses wait in the restaurant’s lobby. They sit on overstuffed sofas and chat as they wait for their tables. Connor manages to halt his run just as he reaches them. He catches sight of Prue just as she pulls on the door to leave.

“What is this?” Connor is standing next to the maître d’s stand, holding the notebook out at her.

Prue turns around. She rolls her eyes and purses her lips.

“What does it look like?” Her head shakes in disbelief. “I thought you’d thank me.”

Her tone is sharper than any knife. Connor is convinced Prue doesn’t have any other way to speak. That said, the sharpest knives make the cleanest cuts. You barely feel them. They slide rather than tear through the flesh.

“So everything went okay with probate?” He clutches the notebook to his side. “My share of stuff went to Dad?”

“Oh, that.” She turns around and pulls open the door. “I got Dad to give his share to me. I’m in a better position to deal with it.”

She is out the door before Connor can collect himself. He just stands there watching the door close. The customers do an admirable job of chatting with each other and waiting as though Connor and Prue were not talking at each other from across the lobby.

“Are you all right?” The maître d’s voice takes Connor by surprise. “Take the night off. It’s not like you haven’t earned one, or ten.”

He turns to the maître d’, now back at her stand. A forced smile breaks his face.

“No, I’ll be fine.” He holds up a hand, as if to press her away. “I just need to get back to work.”

He rushes back into the dining room before she has a chance to respond. The rest of his shift is a blur. Customers are served. Water is transformed into seasoned beef stock then into a powder that is sprinkled on top of an emulsion of onion and gruyere that sits on top of parmesan-coated cracker. Veal shanks become their braised, tender selves and are infused with the flavors of tomatoes, rosemary, and bay leaf. Foams that taste of apple and cranberries float over a bed of puff pastry. Food seems to craft itself.

It hasn’t, because, after the shift ends, he is sweat-soaked, stripped to the waist, and collapsed on the bench in the locker room. The noise of slammed locker doors, zipped zippers, and chatty servers surrounds him. People ask him whether he’s okay as they pass by, and he tells them he’ll be fine in a minute. When he sits up, the locker room is empty. He takes the notebook his sister gave him out of his locker.

His heart starts to pound and his hands shake as he opens the notebook. The hope that bubbles in him makes him queasy. Years of searching and experimenting could be over in an instant because of help from, of all people, his sister. It’s not impossible Mom told Prue her recipes. Prue was the one Mom expected to be interested in cooking. It’s not impossible that Prue would write them down. Writing them down for Connor is a bit of a stretch. Passing Mom’s recipes down, though, would make her look good to their relatives.

When he reads the first recipe, the bubble of hope growing inside him bursts. He riffles through the notebook. The pages rustle past. Spare text in his sister’s airy hand is spread across each page. It’s a definitely notebook of recipes, just not their mom’s.

He snaps the book shut, expecting to dash it against the lockers. Anger is supposed to shudder through him. Instead, he laughs.

His arms squeeze the notebook to his chest. His laughter is a hand saw ripping through wood. Air leaves his lungs before it’s had a chance to enter and tears fill his eyes.

He stops only when he realizes he’s no longer alone. At some point, the handsome band singer, dressed in a T-shirt and jeans, entered the locker room. Connor snaps straight, seated on the bench, the final laugh choked in his throat.

Nick’s gaze sweeps across Connor. It stops at Connor’s tear-filled eyes.

“What did your sister do to you this time?” Nick’s gaze is gentle, as though he actually wants to know. “Would you like a hug?”

Connor smiles as he wipes the tears from his eyes. He shows Nick the notebook.

“What she gave me is absolutely not a notebook of Mom’s recipes.” Connor sets the notebook on the bench. “You know how you can look at a piece of music and know how it will sound?”

“Oh, you can look at a recipe and know how it will taste.” Nick sits next to Connor on the bench. He pats Connor’s knee. “I’m sorry, Connor.”

“No, it’s fine. It’s weirdly well meaning, actually. Anyone else—well, maybe not anyone else here, but anyone else—might believe these are my mom’s recipes and stop trying to recreate them.” Connor shrugs. “That’s just the way my sister is. She’s never going to change.”

Connor starts laughing again. It’s more gentle this time. He’s hunched over, and his shoulders start pumping up and down.

“What’s so funny?” Nick picks up the notebook and starts thumbing through it.

“Mom’s dead. Probate’s settled. If I don’t want to, I don’t have to deal with Prue anymore.” Connor forces the next words out. “And I don’t want to. Does that make me a monster?”

“Then don’t deal with her anymore.” The smile on his face is kind, not cruel. “It doesn’t make you a monster.”

“Um, Nick.” Getting these next words out is like summiting a mountain. “Can I have a ride home? I don’t—”

“Sure. Any time. It’s my pleasure.”

Connor doesn’t invite Nick into his apartment. He wants to, and Nick even looks a little disappointed when Connor doesn’t and just says goodbye instead. The apartment, though, is a mess. Besides, there’s something Connor wants to do tonight, and he needs to do it alone.

Nick’s car disappears down the street. It’s an odd thing, such a big man in such a small car. When Connor first saw it, he wondered how Nick would fold himself into the driver’s seat. Maybe he’ll ask for another ride sometime. Take another crack at figuring that out.

His kitchen is the one neat area in his apartment. His training is too ingrained in him for the kitchen to be anything but pristine. All the surfaces have been wiped down. Everything is in its place.

He opens a window. It’s spring, and the breeze that drifts in is not freezing. The battery pops out of the smoke detector with a practiced ease. He places a stockpot on the floor and puts into it: his dumpling journal, the notebook his sister gave him, and a lit match.

Journal pages char, curl up, and slowly become ash. The scent of steaming dumplings perfume the air. The smell is not the one he remembers from when he was a kid, but it still reminds him of watching his mom cook. She’d roll out tiny balls of dough, fill them, and crimp them so quickly, he never had a chance to work out how to make the dumplings for himself. She always refused to show him, saying she’d always be around to make them for him.

She, of course, will never make them for anyone ever again, and he needs to stop trying to recreate them. Prue, much as he hates to admit it, has a point. That doesn’t mean he won’t say goodbye to her, too.

The notebook pages catch fire. The burning paper smokes. Black rings eat away at each page. Grey wisps stretch up, tangling with one another as they go. A thread of bitter weaves itself into the tapestry of flavors.

Connor sits in front of the fire. Flames lick the sides of the stockpot. Individual tendrils dart up. The fire is a hungry creature licking its prey. The paper curls and shrinks with faint crinkles and crackles. Slowly, he breathes in the fragrant and the bitter as he watches his memories render into ash.

Text copyright © 2019 by John Chu

Art copyright © 2018 by Dadu Shin

Buy the Book

Beyond the El